I had an interesting realization recently: I was three years into my career when I got my first remote job, and it's been about three years since then. I've now spent half my career working in a traditional in-office software development job, and the other half working remotely!

Increasingly, remote work is becoming a common, mainstream thing. Social media pundits have been quick to form and share opinions, and I've seen a lot of misconceptions and misinformation about what "remote work" is, and how it works.

This is part 1 of a two-part blog post series. Today, I'll share what my experience has been like—it'll be an honest look at the ups and downs of remote life. Hopefully, this context will be helpful if you've been considering remote work for yourself!

- Part 1: My experience

Link to this headingClearing up misconceptions

Let's start by getting this out of the way—most people talking about remote work are describing something very different from my experience.

For example, this common refrain:

"Remote work sounds great because you can work from home in your pyjamas, but it's not all it's cracked up to be, because soon you'll discover how isolating it is to spend all day alone"

This discussion is predicated on a false idea, that "remote work" is synonymous with "working from home", and that it means you work alone.

I think it would surprise people just how much my "remote work" lifestyle looks like their "normal office" lifestyle:

- I get up early, shower, change into street clothes, and commute every weekday to an office

- I work from around 9:30am to around 5:30pm, grabbing lunch around 11:45am (gotta beat that lunch rush!)

- I have regular meetings with my coworkers, doing things like pair programming with my peers, or hashing out implementation details with product & design

- I socialize in-person with other folks at the office.

This schedule is not universal to remote workers, and that's kind of the point—the idea with remote work is that it's flexible. It allows you to construct whatever working situation works for you. Plenty of remote workers do work from home (though none that I've met have been the unshaven recluse so often depicted in remote-work discussions), but they do it because that's the situation that works best for them.

Link to this headingDeveloping my working environment

I realized pretty quickly that working from home wasn't going to work for me.

When I started working remotely for Khan Academy, I rented an office at WeWork. It ticked a bunch of boxes, but ultimately it wasn't the right fit. It was rowdy at times. It was also kinda dreary—they keep their lights dim, so there's a perpetual 7pm vibe. Despite having all-glass walls, my office wasn't anywhere near natural light. The office I was renting was small enough that if I stood in the center, I could just about touch all 4 walls without moving.

About a year ago, I switched to a new office.

I'm subletting it from a local Montreal company, located in Old Montreal. It's not really a coworking space; it feels less like a trendy startup incubator and more like a traditional small business. It grants me the perfect level of in-person social interaction; there are always people around I can talk about hockey or the weather with.

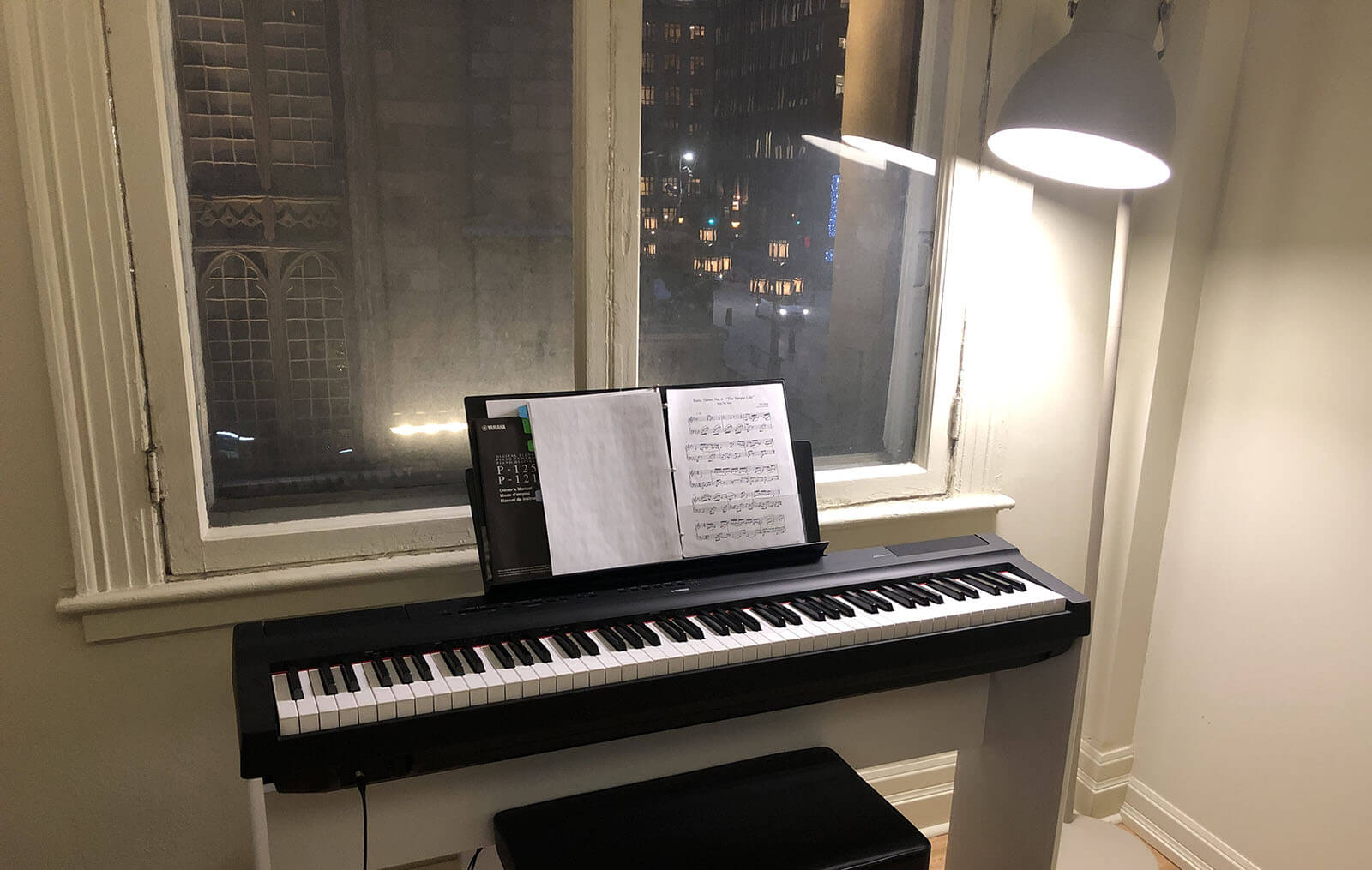

My office is big and bright, featuring tall ceilings and a large window. It overlooks a public square, and I've set up a digital piano in front of it, so I can take frequent breaks and watch tourists meander while I noodle on the keyboard. It's pretty great.

I am very aware that this office is a privilege that many cannot afford—it costs $700 CAD / $525 USD a month. In many cases, though, employers are willing to contribute towards these costs, either in part or in full. And this additional expense is often smaller than the bump in salary folks receive when transitioning to remote work.

Link to this headingNotable differences

For the most part, I've been surprised to see how similar remote work is from in-office work. There are some things that are different, though. Let's look at them in depth.

Link to this headingSalary

I live in Montréal, Québec. According to Payscale(opens in new tab), the average Montreal software developer makes about $65,000 CAD, about $49,000 USD. This is dramatically less than in the Bay Area, where Payscale(opens in new tab) estimates the average salary at around $118,000 USD. That's a 2.4x multiple!

Remote-friendly companies don't always pay Bay Area salaries, but in my experience, they tend to pay quite a bit better than local ones. For example, Buffer pays based on San Francisco rates, and deducts up to 25% for cost-of-living(opens in new tab). This feels pretty harsh to me, and yet it still comes out to a much more generous salary than is common in Montreal.

If you already live in a high-pay, high-cost-of-living area like San Francisco or New York City, working remotely can grant you the freedom to move wherever you'd like. While not everyone can uproot their family and move, it's still better to have the option than not.

Link to this headingMeetings

One of the myths of remote work is that it's "lone wolf" territory, meant for contractors who need little guidance and have little oversight. The truth is that all of my years as a remote worker have been fairly collaborative, working within tight-knit teams to develop and ship features.

As a remote worker, I have roughly the same number of meetings as I did when I worked in-office.

Most remote-friendly companies will have a policy that every meeting room is equipped with video-conferencing software, and every meeting has a Google Hangout or Zoom session created for it. This way, remote folks can join any meeting added to the calendar without meeting organizers having to do anything special.

It can be hard to fully participate, though. It's human nature to interact primarily with the people in the same space as you. As a remote employee, your disembodied, televised head is often floating out of eyeline, off in the background. As conversation picks up, it can be hard to get a word in edge-wise. If you wait for the perfect opportunity, you might never have a chance to speak. And if you decide to interject haphazardly, you'll be the booming voice of God, a gigantic face stretched across a 72" screen, causing heads to swivel around like a mob of startled meerkats. I don't like drawing that much attention to myself.

If you work for a fully-distributed company, this isn't a problem, since everyone's on their own laptop. And many companies are moving to a model where all meeting participants join on their own computer, even those in the same room together. This ensures a level playing field, and makes it much easier for remote participants to participate.

Link to this headingBeing kept in the loop

A concern many folks have about remote work is that inevitably, no matter how much Slack is stressed, two employees will bump into each other in the office and share information or make decisions. Folks in other timezones and countries will miss out on that information, and sometimes this can make it harder to be effective at your job.

I can definitely think of times where, say, I spent a day working on something only to learn that the feature isn't needed anymore... but the thing is, that's happened to me both as a remote worker and as an in-office worker. Communication challenges are not unique to remote work. And the solutions are pretty much the same:

- Daily standups ensure visibility around what everyone is working on, and if they're blocked by something

- Being a good communicator, and being sure to follow up frequently. If I'm picking up a ticket from Jira that hasn't had a comment on it in 4 months, for example, my first step is to contact the stakeholders and make sure the issue is still relevant.

- Working in small ("two pizza"(opens in new tab)) teams, and checking in with teammates frequently

People assume that it's harder to stay in touch with people when you don't work out of the same space, but I'd argue it's the opposite. Tools like Slack let you instantly fire off a message, without worrying if you're interrupting someone deep in concentration. When I worked in-office, I was always hesitant to walk over to someone hard at work. Slack gives me license to talk to people more often, not less.

Link to this headingLoneliness, and forming personal connections at work

Of the articles and social media threads I've read from people who have actually tried remote work, this is the most common issue. For folks who are used to working in an office, it can be hard to transition to a model where you only speak with your co-workers over screens, where there are no Thursday-evening game nights, mini birthday celebrations, or group lunches. In an office, it's easy to spend twenty minutes by the watercooler, just hanging out with your peers. Those serendipitous interactions don't occur remotely, every communication is intentional.

In my case, I've solved for this by renting an office. The people I share this space with technically aren't coworkers—we don't share an employer—but that doesn't stop us from gossiping about the Habs(opens in new tab), currently on their worst losing streak since 1940(opens in new tab), or sharing vacation pictures with each other.

It's also self-evident to me that it's possible to form close personal relationships with remote coworkers—I'm still friends with many folks I worked with at my first remote job! It may not be ideal, but it works. If hit TLC television show 90 Day Fiancée(opens in new tab) teaches us anything, it's that humans are remarkably good at overcoming the artificial nature of long-distance communication.

Another important consideration: depending on where you live, and the size of the organization, you may not be alone in your city! I live in Montreal, a city not really known for being a tech hub, but when I worked at Khan Academy, I had two coworkers that lived here. Once every month or so we'd grab coffee and co-work together, either at a co-working space or at a coffee shop. Many orgs will rent out a small office for cities that reach a certain threshold, blurring the line between "remote work" and "flexible in-office work".

Link to this headingRemote mentorship

Many folks I've spoken to have expressed concern around mentorship; for folks early in their careers, are they at a disadvantage by not being in the same room as the senior devs?

Link to this headingStress and asking for help

I remember when I was about a year into my career, I was working at a local startup and I had gotten myself into a big mess with Git. I was worried I'd accidentally erase all the progress I'd made on the task that day. The senior dev sat right near me—I could walk over and tap him on the shoulder, but what if he was in the middle of something? I imagined the frustration he might feel, watching his mental house-of-cards collapse as his focus evaporated, all because some sheepish junior dev doesn't understand source control.

Now that I'm a senior developer myself, I recognize how silly this thought was—I'm always happy to help when someone needs it! But that fact is irrelevant; junior devs often worry about stuff like that, and that worry can lead to bad outcomes, like not asking for help when it's needed.

There's something to be said for Slack's asynchronous model. It's so much easier to send someone a message, knowing they probably won't see it right away if they're deep in concentration.

Link to this headingReceiving help online

What about the actual getting-help itself? Surely it's better for two devs to sit side-by-side when explaining a problem? I'm not so sure. Tools like Screen Hero (RIP) and Slack's video conferencing let two people share a screen, each with their own connected mouse and keyboard. Pair programming works really well when the "passenger" can use their cursor to indicate a specific line, or draw on the screen using a pencil tool. I expect the tooling will only improve as remote work becomes more common!

Also, I feel like text chat is underrated for stuff like this. It lets the explainer choose their words carefully, and make sure the explanation makes sense. And it provides a permanent transcript that the person being helped can reference in the future, if the explanation doesn't stick.

Link to this headingRemote intern mentorship

One more anecdote: every summer at Khan Academy, we'd hire a class of college interns. Every intern would be assigned a mentor, a point person to provide technical guidance, assign and review work, and generally make sure that the intern was having a happy, healthy, educational summer.

Mentors could either be remote or in-office, and as far as we were able to tell, it made no difference; interns were as likely to succeed regardless of whether their mentor was sitting next to then in Mountain View, or located in a different state or country.

I was an intern mentor myself, and it was incredibly fulfilling! I don't believe being remote was a hindrance at all.

Link to this headingProceed with caution

Despite all of this, I still recommend proceeding cautiously as a junior developer seeking remote work. I've had the privilege of working for stand-out organizations that have put a lot of resources into making the remote culture succeed. If certain conventions aren't in place, it can be much harder to receive mentorship as a remote employee. I'll talk more about this in the next post in this series.

Link to this headingCareer progression challenges

I've had the privilege of working remotely for several different organizations now, and I've seen how different structures can lead to different cultures.

At one role in particular, about 50% of the engineering department was remote, while 100% of the executive team (and most managers) were in-office. A good chunk of the executive team was new to the org, and they had come from organizations that were not remote-friendly. This meant that in-office "individual contributors" (ICs) were able to form relationships with senior leadership in a way that remote workers weren't.

I remember during a particularly contentious period, hearing from an in-office friend that a member of the senior leadership team had come up to them, bewildered to learn that remote workers were unhappy with recent policy shifts. This member of the exec team went to an in-office IC for clarification about how remote folks were feeling, because that's who they knew.

This problematic dynamic was highlighted during performance reviews. As in many organizations, promotions were determined by senior leadership, and the process was not super transparent. When a remote worker is denied a promotion, it's hard not to wonder if personal relationships played a part; after all, wouldn't anyone have a subconscious bias towards the folks they have lunch with every day vs. someone they barely know?

These kinds of "office politics" are not unique to remote workers—at any organization, there's the risk of executives biasing promotions towards folks they like. Even if everyone works in the same space, there's no guarantee that relationships will form equally! And I suspect it's human nature to reach for external factors when trying to understand why we weren't selected for a promotion.

Despite these caveats, career progression can definitely be harder for remote workers if the company isn't fully distributed. In the next part of this blog post series, we'll dig into this a bit more as we learn more about how to find a great remote job.

Link to this headingConclusion

The goal of this blog post was to share my experiences as a remote worker, with the hope that it provides a bit of clarity around whether or not remote work could be a good fit for you. And it's a hard question to answer, since "remote work" can mean so many different things. Very few of the experiences I've had—both good and bad—are universally true for remote work.

Ultimately, looking back, there have definitely been some bumps on my remote journey, but the overall experience has been very positive. I don't expect I'll go back to traditional in-office employment any time soon.

I do think I'm a particularly well-suited person for remote work, though. When I worked in-office, I was on a perpetual mission to find a way to eat lunch alone, without offending anyone or arousing concern. I had wonderful co-workers, but my idea of a perfect lunch is sitting alone in a park, listening to a podcast. In that sense, remote work is a perfect fit for me.

While I do think the concern about isolation as a remote worker is overblown—after all, I'm around people constantly—it is true that it can be harder to form close personal relationships with folks you're working around, rather than working with. Making friends as an adult is tough! If your current social network is comprised primarily of people you work with, and you thrive on that sort of camaraderie, remote work might be more of an uphill climb for you.

Aside from this, I believe the other concerns folks have about remote work can be mitigated, either by customizing your work environment, or finding a company with the right kinds of remote policies for you.

If remote work sounds good to you, my next blog post in this series is all about how to find your first remote job. It covers everything I’ve learned as someone who has been involved in hiring for several remote-friendly orgs, and how to evaluate the “remote-friendliness” of companies during the interview process.

Last updated on

December 2nd, 2019